During his most successful season as a major leaguer, Bobby Byrne had some advice for the children who wished to follow in his footsteps:

“If they asked me I would tell them everything I could to keep them from starting. Not that I knock the profession, but I think it is a poor one to choose, not because of the life itself, but because of its temptation and hardships, and worse than that, the small chances of being successful.”

That answer was given to syndicated journalist Joseph B. Bowles during the 1910 season when he asked Byrne questions about how he started in baseball “in order to help young and aspiring players.”

Despite being the starting third basemen for the defending World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates, and on his way to leading the National League in hits (tied with Honus Wagner) and doubles (178, 43), while hitting a personal-best .296 in 1910, he told Bowles:

“If I had it to do over again I do not think I ever would become a professional ballplayer, in spite of the fact that I love the game and love to play it. I think a young fellow would do better to devote himself to some other line than to take the chances of success in the national game, for even when he wins he loses.”

He talked about how he started, and offered a theory about where the best players come from:

“I wanted to be a ballplayer and was educated at the game in a good school, on the lots around St. Louis. I think that ballplayers develop faster when they are in the neighborhood of some major league team. One or two of the players on a ‘prairie’ team are at every game the big league (team) plays. They see how the game is played, and being at that age as imitative as monkeys, they work the same things on their own teams and teach all the other boys. I have noticed when any city has a pennant winning club the quality of baseball played by the boys and the amateurs in that vicinity are much improved.”

Byrne said because of his time playing on the sandlots of St. Louis, he “picked up the game rapidly,” but said it wasn’t until he began to play professionally, first in Fort Scott, Arkansas, then in Springfield, MO, that he corrected the biggest flaw in his game:

“The hardest thing I had to learn was when to throw. I think I must have thrown away half the games we played before I learned not to throw when there was no chance to get the runner. I think that is one of the first things a young player should learn; to look before he throws and only throw when he has a chance to make a play. The next thing, it seems to me, is to learn to handle one’s feet and to keep in the game all the time, and be in position to move when the ball is hit.”

Even at the pinnacle of his career, the man who discouraged children from following in his path, was also somewhat cynical about his own experience:

“The biggest thing I had learned was that, no matter how far a fellow gets up in the business, there still is a lot he does not know, and by dint of watching and learning I held on, and still am learning and willing to learn. When I know it all I’ll quit, or be released.”

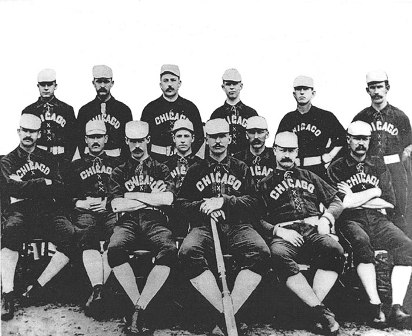

Byrne continued “learning” for seven more seasons, and the end of his career was fitting for someone who warned that a young man should steer clear of baseball because “even when he wins he loses.” After being acquired on waivers by the Chicago White Sox in September of 1917, he appeared in just one game, on September 4. He was with the team when they clinched the pennant 20 days later; and was released the day after he appeared in the team photo commemorating their American League Championship.

White Sox team photo after clinching 1917 pennant, Byrne is fourth from right in second row–he was released the following day.

While the Sox were beating the Giants in the World Series, Byrne was back in St. Louis operating a bowling alley. After three years away from baseball, he managed minor league teams—the Miami (OK) Indians and Saginaw (MI) Aces—in 1921 and ’22 before returning again to the bowling business.

His admonition against professional baseball didn’t stop his two sons from having their own brief minor league careers; Bobby played for several clubs between 1939 and 1941, and Bernie (listed as “Byrnes” on Baseball Reference) played for the Paragould (AK) Browns in the Northeast Arkansas League in 1940. Both had their careers interrupted by WWII, Bernie was an airforce fighter pilot in Asia, while Bobby was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal and Purple Heart while flying for the airforce in the Mediterranean Theater.

Leave a comment