James Palmer O’Neill was the President of the 1890 Pittsburgh Alleghenys—one of baseball’s worst teams of all-time. With mass defections to the Pittsburgh Burghers of the Players League, the club won four of their first six games, then began a free-fall that ended with the team in eight place with 23-113 record.

O’Neill, who held an interest in the club, but bought controlling interest from Owner William Nimick before the 1891, kept the team afloat during that disastrous 1890 season, and according to The Pittsburgh Dispatch, never lost his faith in the prospects of National League baseball in the city right through the final road trip:

“(The team) landed at Jersey City, bound to play the last series of the disastrous season…They had great difficulty in raising the money to pay ferryboat fares to Brooklyn and things were awfully blue. It was raining hard when I met Mr. O’Neill later that morning at Spalding’s Broadway store, and the prospects of taking the $150 guarantee at the game in the afternoon were very slim…(reporters) asked Mr. O’Neill about his club and the outlook for the League.

‘”Never better! Never Better! We shall come out on top sir, sure. We’ve got the winning cards and we mean to play them.’”

The paper said O’Neill’s luck changed that day as “he wore his largest and most confident smile, and used the most rosy words in his vocabulary…such pluck compelled the fates to relent.”

The rain stopped and O’Neill was able to leave Brooklyn “with $2000 or more in his clothes,” to meet expenses.

Before the 1891 season, O’Neill told Tim Murnane of The Boston Globe, just how difficult it was to run a National League club during the year of the Brotherhood:

“I think I could write a very interesting book on my experience in baseball that would be worth reading. How well I remember the opening game in Pittsburgh last spring, and how casually President Nimick was knocked out—and O’Neill laughed heartily at the thought of Nimick’s weakening

“After witnessing the immense crowd of nearly 10,000 people wending their way to the brotherhood grounds, Nimick and I went to the league park. As we reached the grounds, Nimick walked up to the right field fence and looked through a knot hole. ‘My God,’ said he, and he nearly fell in a heap at my feet, ‘Can it be that I have spent my time for 10 years trying to build baseball up in this city and the public have gone entirely back on me?’”

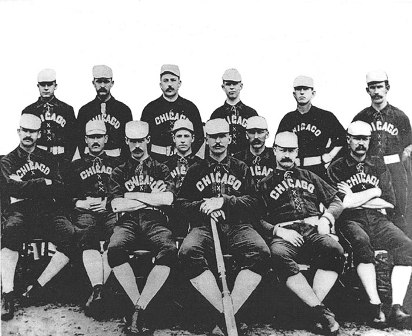

O’Neill trying to catch a championship, 1891

O’Neill said:

“I looked and could see about two dozen people in the bleachers, and not many more in the grand stand (contemporary reports put the attendance at 1000). Nimick and I then went inside the grounds, and when the bell rang to call play we started up the stairs to our box, carrying the balls to be used in the game. When about half way up, the president staggered and handed me the balls. I went up to throw one out for the game. Nimick turned back, went home without seeing the game, and was not in humor to talk base ball for several weeks.”

O’Neill then told how he managed to keep the team going for the entire season while Nimick planned to fold the team:

“When he came around about four weeks later it was to disband the club, throw up the franchise and quit the business. I talked him into giving me an option on the franchise for 30 days. When the time was up I put Nimick off from time to time, and as I didn’t bother him for money he commenced to brace up a little. I cut down expenses and pulled the club through the season, and now have the game on fair basis in Pittsburgh, with all the old interests pulling together.”

Despite the near collapse of the franchise—or maybe because the near collapse allowed him to get control of the team—O’Neill had good things to say about the players who formed the Brotherhood:

“I have great admiration for the boys who went with the Players’ League as a matter of principle, and will tell you one instance where I felt rather mad. About the middle of the season, Captain Anson was in Pittsburgh and asked me if I couldn’t get some of my players to jump their contracts (to return to the National League). “All we want,’ said Anson, ‘is someone to make the start, and then (Buck) Ewing, (King) Kelly, (Jimmy) Ryan, (Jim) Fogarty and other will follow.’

“I told Anson that I had not tried to get any of my old players back since the season started in, but that Jimmy Galvin was at home laid off without pay, and we might go over and see how he would take it. The Pittsburgh PL team was away at the time.

“We went over to Allegheny , where Galvin lived, and saw his wife and about eight children. They said we could find him at the engine house a few blocks away, and we did. Anson took him to one side and had a long talk, picturing the full downfall of the Players’ League and the duty he owed his family. Galvin listened with such attention that it encouraged me. So I said: ‘Now, Mr. Galvin, I am ready to give you $1000 in your hand and a three year contract to return and play with the League. You are now being laid off without pay and can’t afford it.’

“Galvin answered that his arm would be all right in a few days, and that if (Ned) Hanlon would give him his release he might do business with me, but would do no business until he saw Manager Hanlon. Do what we would, this ball player, about broke, and a big family to look out for, would not consent to go back on the brotherhood.”

Galvin

O’Neill said he told Anson after the two left Galvin:

“’I am ashamed of myself. This player has more honor than 99 business men out of 100, and I don’t propose any more of this kind of business.’ I admire Galvin for his stand, and told Anson so, but the Chicago man was anxious to see some of the stars make a break so the anxious ones could follow.”

O’Neill, after he “lit a fresh cigar,” told how Murnane how he negotiated with his players:

“At the close of (the 1890) season (George “Doggie”) Miller came to me and wanted to sign for next year, as he had some use for advance money. I asked him how much he thought he was worth, and he said $4000 would catch him.

‘”My goodness son, do you what you are talking about?’ said I, and handing him a good cigar asked him to do me a favor by going home, and while he smoked that cigar to think how much money was made in base ball last season by the Pittsburgh club. I met Miller the next day at 3 o’clock by appointment, and he had knocked off $800, saying he thought the matter over and would sign for $3200.

“’Now you are getting down to business,’ said I.”

O’Neill sent Miller home two more times, and after he “smoked just for of my favorite brand,” Miller returned and signed a three year contract at $2100 a season.

O’Neill said:

“You see that it always pays to leave negotiations open until you have played your last card.”

Murnane concluded:

“For his good work for the league and always courteous treatment of the players’ league, Mr. O’Neill has the support of not only his league stockholders, but such men as Hanlon, John M. Ward, and the entire Pittsburgh press. He has the confidence of A.G. Spalding, and is sure to give Pittsburgh baseball a superior quality next season.”

Reborn as the Pirates under O’Neill, the club improved slightly in 1891. O’Neill, who according to The Pittsburgh Press, lost as much as $40,000 during the 1890-91 season “a blow from which he never recovered financially,” left Pittsburgh to start the Chamberlain Cartridge Company in Cleveland; he returned to Pittsburgh and served as president of the Pittsburgh Athletic club—which operated the Pirates—from 1895-1898.

He died on January 6, 1908. The Associated Press said in his obituary:

“(He was) known from coast to coast as the man who saved the National League from downfall in 1890, ‘the brotherhood year.’”

.

Leave a comment