Floto on Baseball’s Most Powerful Men

Otto Clement Floto was one of the more colorful sportswriters of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century’s. The Denver Post’s Woody Paige said of the man who was once worked for that paper:

“In the early 1900s Floto was The Denver Post’s sports editor and a drunk, barely literate, loud-mouthed columnist–sounds like a description of that guy in my mirror–who didn’t believe in punctuation marks, wrote about fights he secretly promoted on the side, got into shouting matches with legendary Wild West gunman–turned Denver sportswriter–Bat Masterson.”

Floto, in 1910, provided readers of The Post with his unvarnished opinion of baseball’s most powerful figures:

“John T. Brush—The smartest man in baseball, but vindictive.

Garry Herrmann—Smart, but no backbone; the last man to him has him.

Ban Johnson—Bluffs a great deal and makes it stick. Likes to talk.

Charles Comiskey—Shrewd as can be.

Connie Mack—Shrewd and clever; knows the game better than anyone.

Charles Murphy—A hard fighter, but backs up at times.

George Tebeau—More nerve than any other man in baseball, very shrewd.

Barney Dreyfus—Smart, but always following, never leading.

As for John McGraw, Floto allowed that the Giants’ manager was “Pretty wise,” but attributed his success to the fact that he “has lots of money to work worth.”

Too Much Money for Players, 1884

The Cleveland Herald was not happy when pitcher Jim McCormick jumped his contract with the Cleveland Blues in the National League to the Union Association’s Cincinnati franchise. Although teammates Jack Glasscock and Charles “Fatty” Briody also jumped to Cincinnati, the paper saved most their anger for the first big leaguer to have been born in Scotland.

The paper noted that McCormick, who was paid $2500 by the Blues, had received a $1,000 bonus to jump:

“(A) total of $3,500 for joining the Cincinnati Unions to play the remainder of the season. This is equal to $1750 a month, which again divided makes $437.50 a week. Now McCormick will not play oftener than three times a week which makes his wages $145.83 per day for working days. The game will average about two hours each, so that he receives for his actual work no less than $72.91 an hour, or over $1.21 a minute for work done. If he was not playing ball he would probably be tending bar in some saloon at $12 a week.”

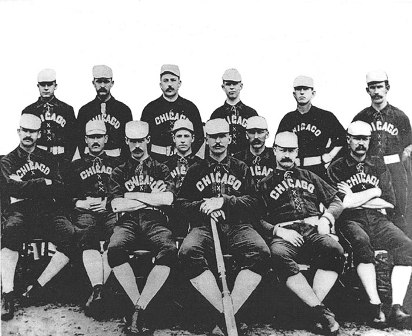

McCormick was 21-3 with a 1.54 ERA in 24 games and helped pitch the “Outlaw Reds” to a second place finish in the struggling Union Association. After the Association collapsed was assigned to the Providence Grays, then was sold to the Chicago White Stockings. From July of 1885 through the 1886 season McCormick was teamed with his boyhood friend Mike “King” Kelly—the two grew up together in Paterson, New Jersey and were dubbed “the Jersey Battery” by the Chicago press—and posted a 51-15 record during the season and a half in Chicago, including a run of 16 straight wins in ‘86.

He ended his career with a 265-214 record and returned home to run his bar. In 1912 John McGraw was quoted in The Sporting Life calling McCormick “the greatest pitcher of his day.”

The pitcher who The Herald said would otherwise be a $12 a week bartender also used some of the money he made jumping from Cleveland in 1884 the following year to purchase a tavern in Paterson.

Not Enough Money for Owners, 1885

In 1885 J. Edward “Ned” Allen was president of the defending National League Champions –and winners of baseball’s first World Series—the Providence Grays. He told The New York Sun that baseball was no longer a profitable proposition:

“The time was when a man who put his money into a club was quite sure of coming out more or less ahead, but that is past. When the National League had control of all the best players in the country a few years ago, and had no opposition, salaries were low, and a player who received $1,500 for his season’s work did well. In 1881, when the American Association was organized in opposition to the league, the players’ salaries at once began to go up, as each side tried to outbid the other. When the two organizations formed what is known as the National Agreement the clubs retained their players at the same salaries.

“Several other associations were then organized in different parts of the country and were admitted under the protection of the National Agreement. This served to make good ball-players, especially pitchers, scarce, and forced salaries up still higher, until at the present time a first-class pitcher will not look at a manager for less than $3,500 for a season. (“Old Hoss”) Radbourn of last year’s Providence Club received the largest amount of money that has ever been paid to a ball-player. His wonderful pitching, which won the championship for the club, cost about $5,000 (Baseball Reference says Radbourn earned between $2,800 and $3,000 in 1884), as did the work of two pitchers and received the pay of two.

“Some of the salaries which base-ball players will get next season are; (Jim) O’Rourke, (Joe) Gerhardt, (Buck) Ewing and (John Montgomery) Ward of the New York Club, $3,000 each. (Tony) Mullane was to have played for the Cincinnati Club for $4,000 (Mullane was suspended for signing with Cincinnati after first agreeing to a contract with the St. Louis Browns). (Fred) Dunlap has a contract with the new League club in St. Louis for $3,400. These are only a few of the higher prices paid, while the number of men who get from $2,000 to $3,000 is large. At these prices a club with a team costing only from $15,000 to $20,000 is lucky, but it has not much chance of winning a championship. To this expense must be added the ground rent, the salaries of gate-keepers, and the traveling expenses, which will be as much more.

“As a high-priced club the New York Gothams leads, while the (New York) Metropolitans are nearly as expensive. The income of these two clubs last year was nearly $130,000, yet the Metropolitans lost money and the New York Club (Gothams) was only a little ahead. The first year the Metropolitans were in the field(1883) their salary list was light, as were their traveling expenses, and at the end of the season they were $50,000 ahead.”

The Grays disbanded after the 1885 season.

2 Responses to “Things I Learned on the Way to Looking up other Things #11”