DeHart Hubbard was the first African American Olympic gold medal winner in an individual event—running long jump,1924—and owned the Cincinnati Tigers, who played as an independent team from 1934-36, and were members of the Negro American League in their final season, 1937.

DeHart Hubbard

In 1944, Hubbard authored a plan to capitalize on black baseball’s, “opportunity of becoming firmly entrenched as an outstanding and progressive enterprise, reflecting credit in Negro people.”

He warned that promoters and “booking agencies” controlled Negro League baseball and said the owners held no power.

Wendell Smith, sports editor of The Pittsburgh Courier endorsed much of Hubbard’s plan which he said would relieve the Negro Leagues “of many of the Barnum and Bailey policies, with which we are all familiar.”

Wendell Smith

Smith used Hubbard’s “logical and credible” suggestions to improve “solve many of the problems with Negro baseball,” to revisit his opposition to one team–under the headline: “The Case of Mr. Pollock’s Clowns,” Smith wrote:

“In line with Hubbard’s program for a clearer interpretation of the policies of Negro baseball, I submit the case of the Negro American League aggregation known to one and all and the ‘Clowns.’ This team is owned by Syd Pollock of Tarrytown, NY, a theater owner, who is reaping profits out of Negro baseball.”

Smith had previously—in 1942 and 1943 columns–referred to the Clowns as a “fourth rate Uncle Tom minstrel show,” and said, “I believe most Negroes resent the Clowns and their implication.”

As a result of Smith’s 1942 comments, Pollock sent The Courier what Smith called “a bristling letter,” calling Smith’s claims about the team were “founded in filth and untruths.” Pollock claimed in the letter that the club was still owned by Hunter Campbell, a black man who founded the team as the Miami Giants in 1935 and by most accounts had sold his interest to Pollock in 1939.

Syd Pollock

To this claim, Smith said, he was unable to “establish ownership” of the club, but that if Campbell still had an ownership stake:

“(T)he finger of scorn is all the more direct and penetrating. As a Negro, Campbell should realize the danger in insisting that his ball players paint their faces and go through minstrel show reviews before each ball game.”

Smith also noted during the 1942-43 exchange that Pollock “Cancelled his subscription to The Courier.”

His opinion of Pollock and his team had not softened in 1944:

“Like many other white people, Mr. Pollock has a misconception of the value of Negro performers…(He) believes, apparently that the only way to make a success out of Negro baseball is to tack such an infamous name a “Clowns” onto his hired hands and send them around the country putting on showboat skits before ball games.”

Smith said he had spoken to Pollock frequently and considered him “a fine and well-meaning man,” but said:

“(Pollock) still seems to believe that the only way to make the ‘Clowns’ popular is to send them into a song and dance.

“Why he insists that this is the way to baseball success, I don’t know, because he certainly hasn’t been able to make any one city or community accept the team for any length of time. Mr. Pollock has put his baseball circus in Miami and Cincinnati, but neither city accepted them. Now he has moved his team to Indianapolis, where he hopes he’ll find more hospitality and finally a stationary home.”

Smith predicted that because “Mr. Pollock insists on having his ‘Clowns’ stress clowning on the baseball field, he won’t find a home,” and called on Negro American President Dr. John B. Martin, to explain to Pollock the, “broad and distinct difference between baseball and slap-stick comedy…The next thing we know, Mr. Pollock will have his ball club playing in a tent with an elephant doing the pitching.”

Smith kept up his criticism of Pollock later that summer when the Clowns’ owner was fined $250 by the league for his team walking off the field during a game in Memphis in June:

“It is gratifying to know that (President) Martin had the courage to give the arrogant Syd Pollock and his urchins a spanking.”

Smith took the attack on Pollock further:

“If there were such a thing as a baseball fascist, we’d expect to find Syd Pollock on the list, because he did more than any other person in the sports world to belittle the plight of Ethiopia while it was being raped by Italy. My. Pollock carried on the ingenious idea of calling his club the ‘Ethiopian Clowns.’ He painted his players’ faces in diverse colors, made them go into a song and dance on the playing field, and in general was a party to what might be termed a ‘burlesque’ campaign that belittled the tragedy of Ethiopia.”

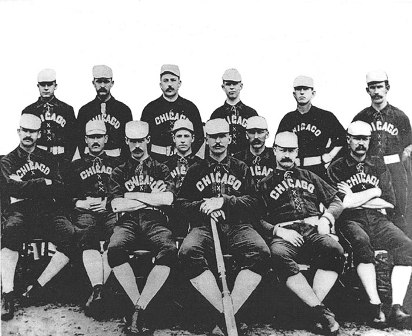

Ethiopian Clowns, 1936

Smith would continue to take shots at the Clowns and Pollock throughout the 40s while fighting for integration of organized baseball. In 1945, he congratulated Detroit promoter John Williams, who refused to book the Clowns in Detroit because, “he vigorously objects to the ‘Uncle Tom’ shows they put on,” he also lauded outfielder Jack Marshall who had refused to re-sign with the team because of “the monkey-shines owner Syd Pollock requires of his players.”

Despite Smith’s efforts, which continued after integration and after he moved to The Chicago Herald-American—where he again referred to Pollock’s “Minstrel Show,” in the 1950s, the Clowns continued barnstorming long after Smith called for their demise, and for more than a decade after Smith’s death in 1972.