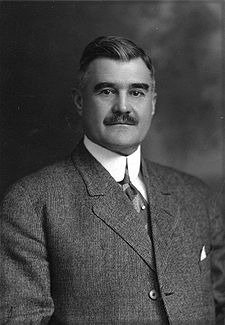

Upon being named president of the National League in 1910, Thomas Lynch spoke to a reporter from The New York Telegraph about his experiences as an umpire from 1888 to 1902:

“The personal discussions and individual adventures I had with the old-time ball players were innumerable. In those days umpires were not nearly as well backed up as now, and they frequently had to depend on nerve and a good right swing to protect them. Brawling players—usually good fellows off the field, but wild to win by any means—were many and they made the umpire’s life a burden.”

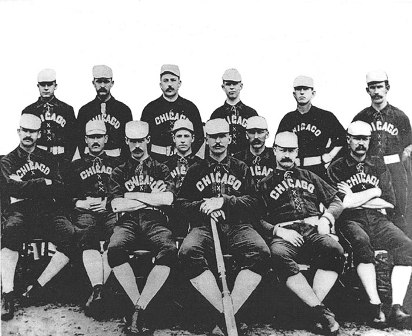

Lynch said, “The old Cleveland Cub,” the 1888 Spiders, who included Jesse Burkett, Cupid Childs, Jimmy McAleer, and Chief Zimmer stood out as, “pests when it came to nagging umpires.”

The team, he said, “had a queer trick—testing the umpire’ disposition to find out how far they could go and get away with.”

Burkett would approach Lynch:

“’How do, Mr. Lynch?’ He would say, ‘Nice weather we’re having. Guess we’ll have a pretty good game this afternoon.’

“If I happened to be feeling good-natured and sociable, I would naturally answer, ‘Sure. Glad to see you looking so well,’ or something along those lines.”

Burkett would then tell his teammates, “(He’s) feeling fine and happy. Work on his good nature, pals.”

Lynch said s from there, “They tried to slip something over on me every inning and tried to help my affable mood help them along.”

The would also argue louder and “start an awful howl” when disagreeing with a call, “Figuring that I was feeling too good natured to fine the or put them out of the game, they would fairly riot around me for five minutes after every decision that displeased them.”

If Lynch were in a bad mood when Burkett approached:

“Being bad-tempered or out of humor, I would either pay no attention to this greeting or answer with a grunt.”

In that case, the team was told:

“Cheese it fellers…He’s got a horrible grouch on. Better let him alone this afternoon.”

Lynch said he was not aware of what was happening despite Cleveland doing the same to every umpire, until “Zimmer put me wise,” later in the season

Lynch said he always thought it “best not to hand then any personal abuse,” and was proud to have “never called a ballplayer any names.”

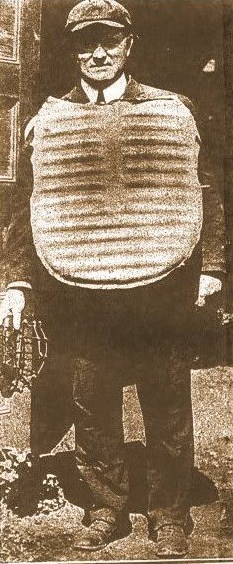

The new league president called his former colleague Tim Hurst—the two were members of the National League umpire staff together from 1891-1902— “a unique and amusing character of the diamond,” who “played the umpiring game the other way,’ and:

“(B)elieved in answering ballplayers in their own coin.”

When players argued with Hurst, “with any ornamental language,” the arbiter would, with his “ready Irish wit,” would reply in a manner “that left the offender dazed and a target for the ridicule of his own pals.”

Hurst also “wouldn’t hesitate to soak a ballplayer with his good right mitt or on a decision when he thought it was necessary to teach a disturber a lesson.”

He told of a run in Hurst had with the Orioles, “a fearful gang when it came to fighting umpires,” in Baltimore:

“One afternoon the Orioles were being trimmed and were fighting like wild cats. Presently they bubbled over and burned up the grass around the home plate with their phraseology. Tim answered them in kind, stormed all of them, chased one or two, and still they kept troubling.

“At last, Jake Stenzel slid for the plate. He looked safe to the stand and to everybody, in fact, but Tim. ‘You’re out,’ yelled Hurst. Jake sprung up and rushed at Hurst.

“’ What did you call me out for, you spiflicated rother of a lop-eared mule?’ howled Jake.

“’I called you out, you hungry-looking sheep-stealing Dutchman,’ said Tim, ‘because your face gave me a pain. Now get out of the game.’ And Jake departed.”

Lynch retold a version of a story repeated frequently, with some different details, over the years about a game in Cleveland against the Orioles. Patsy Tebeau of the Spiders indicated the “wild-eyed crowd” with only a rope separating them from the field, and said to the umpire:

“The first bum decision you give, Tim, we’ll cut those ropes and let the mob in on you.”

Hurst did not respond. Later:

“Joe Kelley came up. He hit a long foul, way off the line. ‘Fair ball,’ yelled Tim. ‘Run, Joe, run,’ Then turning to Tebeau, he shouted, ‘Now cut the ropes you four-flushing hyena.”

Hugh Fullerton told essentially the same story in 1911 in “The American Magazine.” In his version was a game against Chicago and Jimmy Ryan was the batter who hit the foul home run. In this version, as Ryan rounded the bases,

“Hurst turned and shook his fist at Tebeau, shouting: ‘Cut the ropes, ye spalpeen, cut the ropes.”